A many of you know, I’m writing a book about group dynamics that will be published next summer. The exciting news is that the end is in sight! (That’s also the terrifying news — there’s not much time left! Ahhh!!). Because I am contractually obligated to do so, I wrote a bunch of words, formatted them to seem book-like, and sent the words to my editors.

(Note: I didn’t need to be obligated - writing the book has been fun. Mostly.)

Last month, I had a mini-celebration when I submitted my manuscript to my editors. I think it was a cheese scone and high-five with my wife or something (it is even nerdier than it sounds—she’s German, so she high-fives in German. And I’m me!).

But, after you submit a book manuscript, editors don’t say “Great job! No notes!” Instead, they quite rightly point out all the places where my book-like substance hasn’t quite congealed into a final product. Which means more work for me.

For most creative workers, feedback is a necessary evil. In academia, we know an invitation to revise and resubmit a manuscript is the best we can hope for—even after months or years of work on a project. And those revisions can take longer than the first draft. So our celebrations are often tempered with a sigh.

Yet getting help and feedback is one of the most important parts of the creative process. Part of any creative endeavour is making something, finding people who will tell you honestly what’s working and what isn’t, and then re-making large swaths of what you’ve painstakingly created. Accepting that reality is essential if you want to do creative work. Kill your darlings, and all that.

I’ll come back to help, advice, and feedback in a later post. After all, that’s one of my main areas of research. (see here, here, and here for instance). But it’s my newsletter, and I want to talk about what has been on my mind: titles.

For the last three years, my book-like substance has been called Group Think: How Being Together Shapes Our Lives. The title emerged from a funny mistake. At least it is funny if you spend most of your waking hours thinking about group dynamics.

Anyway, I was writing about groupthink, Irving Janis’s term for the conformity pressure that leads groups of otherwise capable individuals to make stupid decisions. I wrote a piece for The Conversation about it. And an editor there changed my spelling from “groupthink” to “group-think” when it was published online.

My agent, Max Edwards, thought Group Think (two words) was a catchy title for a book about group dynamics. But the academic in me recoiled because that’s already an official academic term. Even if it is one that is out of fashion and lost much of its original meaning. And, just as importantly, it is a pejorative term - it is supposed to be a diss. Why would we call my book that?

Max insisted he could sell Group Think more effectively than the many, many other titles I suggested. And, gosh, he was right! We had a bunch of meetings with publishers. We had an auction for the book! And, we have fabulous publishers for it both in the US (Avery) and in the UK (Simon & Schuster).

Now that the book is mostly written, we are talking about making it real—covers, titles, publicity, oh my! And, upon reflection, the publisher decided that the negative connotation of groupthink was too much to overcome.

But here’s something you may not know: When we sold the proposal, we also sold the rights to title the book. As the author, I do not have final say over the title. The publisher does. Group Think (two words) was dead.

And, honestly, that’s a good thing.

The problem I, as the author, have, is that I already know what the book is about. Something meaningful to me might confound a new potential reader. And there is literally no way for me to un-know my own creation to the point where I can have the experience of encountering it for the first time.

Even if I could, we aren’t trying to sell the book to people like me - academics who have spent their professional lives studying the topic. So I have neither the distance nor the perspective to deeply understand the best title for the book.

All the same, I tried! I took to heart IDEO’s classic brainstorming advice to “go for quantity” and came up with hundreds of potential titles. And, when brainstorming, I always think of research that suggests the most common problem in idea generation is that people give up to soon. For instance, organizational psychologists Brian Lucas and Loran Nordgren found that most people undervalue persistence in creative work (and put too much faith in “aha” experiences, known as insight). So I fired up ChatGPT, grabbed some friends, and generated way more alternatives than I realistically could have needed.

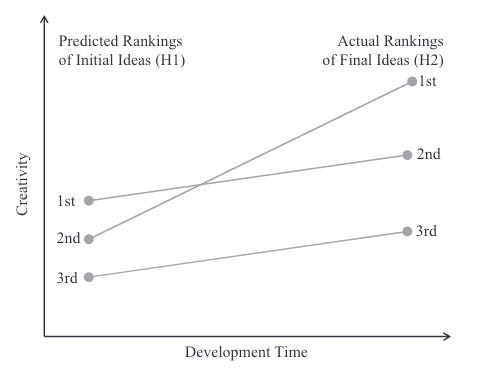

Unfortunately, research also suggests that, if I choose my favorite idea, it isn’t likely to be the best one. Creators often mis-estimate the potential of their own ideas. University of Michigan professor Justin Berg conducted a study where he asked creators to rank the potential of their own initial ideas—before they completed work on them. Then, they developed all the ideas and submitted them to experts for evaluation.

Suprisingly, when experts rated the final, developed ideas, it revealed creators were usually wrong about their initial rankings of their ideas potential. Their highest potential idea was usually the one the rated second by the experts.

Now, you can’t live life by always taking the idea you like second best. For me, the lesson of this research is: you can’t fully trust your own judgement of your ideas. When evaluating our own ideas, we suffer from what Berg calls “myopia”: we’re too close to our ideas and can’t see the forest for the trees.

Nonetheless, if you generate ideas for about about twice as long as you think you should, there’s probably a good one in there. But, to figure out which ideas are most promising, you need to enlist those with a bit more distance from it. And its best, if you can enlist those who are closer to your potential audience.

That’s what I did in my conversations with my editors and agent, as well as many friends and family members. We have a title I feel good about now.

What is the title, you ask? You’ll have to wait to find that out until later. And, when you find out, just say you love it - I can’t change it anyway.

Odds and ends

A huge thank you to the great Substack publications that recommend The Fishbowl: Love Factually Podcast, Provoked, Moral Understanding, Relational Riffs, and attention activist. I recommend you subscribe to all of them now BEFORE IT IS TOO LATE!

And thank you to the many of you who made the trip out to London for the Creativity Collaboratorium! I can’t tell you how gratifying it is to have so many people tell me its their favorite conference. Love ya all!

Come see my favorite singer, Carola Emrich-Fisher (who, coincidentally, I am married to) perform with the Felici Opera on Sunday, September 22.

I dropped off my daughter at university a couple weeks ago. I am very old.

I’ll be jamming with Suedejazz Collective again at 91 Livingroom next Friday, September 27. Get tickets early, as these have a tendency to sell out. The last few times have been great, so come down! Here are some clips where you can see me from a few months back:

References

Berg, J. M. (2019). When silver is gold: Forecasting the potential creativity of initial ideas. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 154, 96–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2019.08.004

Fisher, C. M., Amabile, T. M., & Pillemer, J. (2021). How to Help (Without Micromanaging): New research points to three strategies. Harvard Business Review, 99(January/February). https://hbr.org/2021/01/how-to-help-without-micromanaging

Fisher, C. M., Pillemer, J., & Amabile, T. M. (2018). Deep help in complex project work: Guiding and path-clearing across difficult terrain. Academy of Management Journal, 61(4), 1524–1553. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2016.0207

Landis, B., Fisher, C. M., & Menges, J. I. (2022). How employees react to unsolicited and solicited advice in the workplace: Implications for using advice, learning, and performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 107(3), 408–424. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000876

Lucas, B. J., & Nordgren, L. F. (2022). Lay people’s beliefs about creativity: Evidence for an insight bias. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 26(1), 6–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2021.09.007