Issue 7: How I Became a "Good" Writer

I used to be a bad writer. Here's how I turned it into a strength.

Writing did not come naturally to me. In elementary school, I found putting pen to paper painful — I chewed up pencils, managed to crumple any scrap of paper I laid hands on, and desecrated it with my abysmal penmanship.

This hurt my mother and her calligraphy pen collection right in the soul. A second-grade teacher at the time, she’d sit me down at the table to trace letters, write within the lines, and try not crumple up the damn paper. (Note: This did not work.)

But bad handwriting wasn’t the only reason I struggled as a young writer. My thoughts flow in abstract spirals, not straight lines. If I’m lucky, I think of the end, then the beginning, then the middle. Bits of ideas emerge out of a fog; I try to grab them and assemble them into something coherent. Even my dreams are non-linear, in which my Sandman rewinds and tweaks the same moment over and over. There’s little plot to be found in Colinland.

Compounding matters, I was obsessed with sounding smart. I’m told my favorite word as a four-year-old was “Actually.” Ten-year-old Colin read a dictionary cover-to-cover to harvest impressive specimens likely to amaze and confuse. I memorized overly complex ways of saying simple things, like “It is fruitless to attempt to indoctrinate a superannuated canine with innovative maneuvers.”

All this led to obfuscatory, labyrinthine, and downright confuzzling writing.

The advent of word processors improved things. Unlike pencil-and-paper, I could move text around the page! As an abstract thinker obsessed with sounding smart, these modest improvements in my writing put me on a collision course with academia.

I got good enough at writing that Harvard let me into their PhD program with zero background in the component disciplines (social psychology and business, in my case). But now I was the pomeranian with its chompers around the bumper of a semi-truck. Publishable manuscripts are worlds away from admissions essays.

The sheer scale of articles overwhelmed my non-existent writing process, scattering curly ideas across scores of pages. I’d end up with 60 pages of loosely related ideas. That sounds like a nearly finished manuscript - I just need to cut it down to 40 pages, right? But after weeks or months of working, I’d discover that what I thought was nearly complete was actually variations on the same few ideas.

In short, I was lost. But I was too ashamed to admit it, even to myself.

I got through six years of a PhD program and about three years into my first tenure-track job before I admitted the depths of my problems. I had plenty of good excuses for my stunted professional progress. I was always behind because of my lack of pre-PhD training. Both my kids were born when I was in grad school. I moved back to Redmond for a year to care for my dying mother, who’d fallen suddenly ill with cancer.

The publish-or-perish demon didn’t care, however. If I wanted to stay in this devilish game, I’d have to learn the rules.

So here’s how I turned things around.

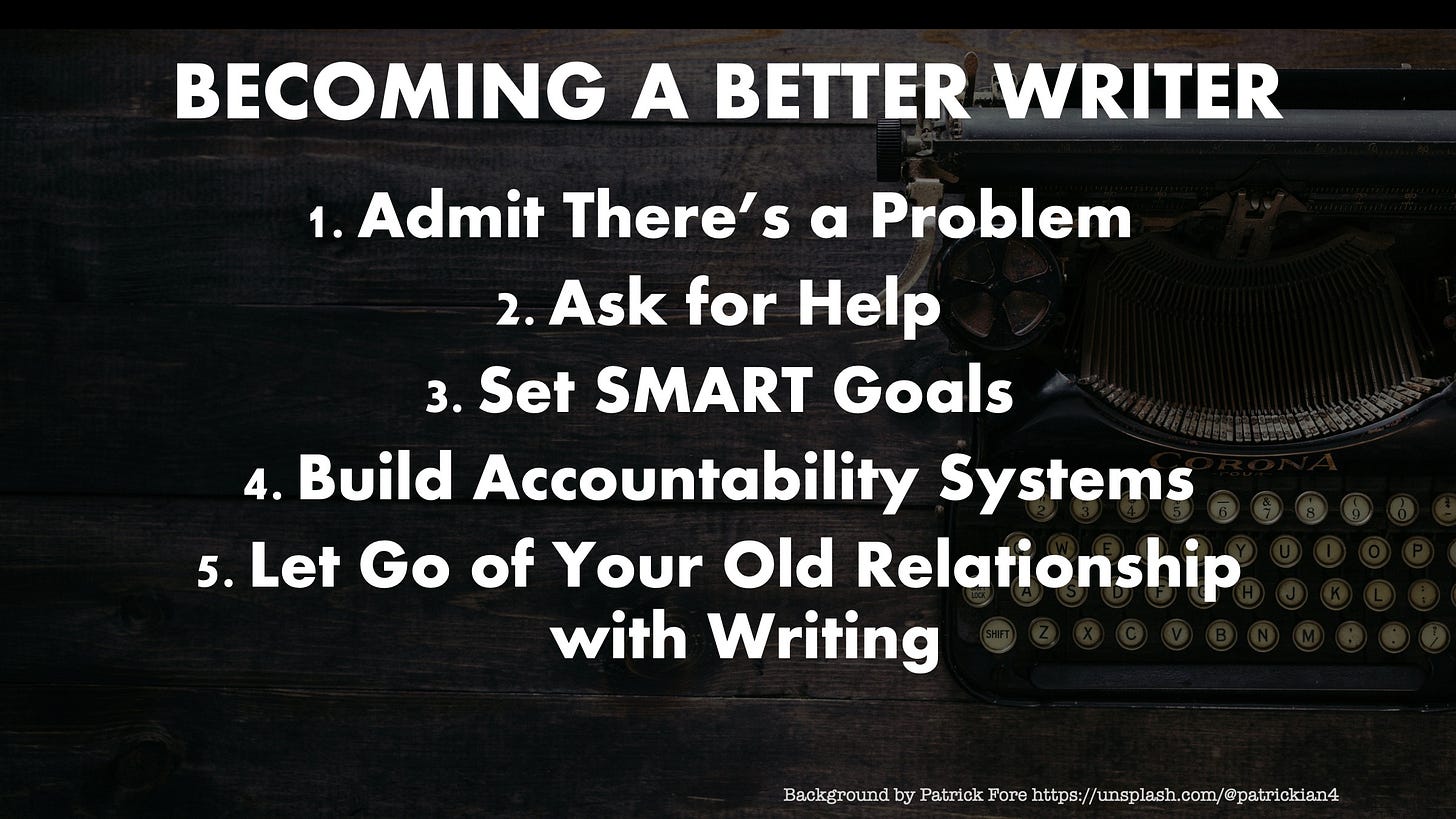

1. Admit there’s a problem

Although the tenure track at demanding institutions is stressful, it does one thing well: It provides clear feedback. At my first institution, I knew I needed at least four publications in top journals to even have a conversation about promotion; it was much safer to have six or seven. To feel secure, I needed to publish an article in a top journal about once per year.

It was easy to compare this metric with my actual productivity of zero. I was able to make excuses for the first couple of years. “I’m learning to be a faculty member.” “I created three new courses.” “Four papers are almost done (look at all the pages!)!”

But, as each year passed, I felt worse and worse. I believed in my ideas and results. I liked every aspect of the academic career. Except writing. Which led me to the second step.

2. Ask for help

I was open with my friends and junior colleagues that I was struggling. By sharing my concerns, I discovered I wasn’t alone. Others had similar problems.

My junior faculty colleagues and I started a writing group that usually turned into venting about our struggles as much as anything else. (Huge shout out to Emily, Erin, Michelle, and Bess!). One of them worked with an academic writing coach! I decided to give it a try.

I had two different coaches. The first had a counseling background. She helped me to figure out what I wanted out of my career and to reflect on my practice.

Eventually, I wanted more nuts-and-bolts support to find a sustainable writing process. My second coach, Moira Killoran, seeded the process I still use fifteen years later. The basics won’t be suprising: You set goals, reflect on your progress toward them, and experiment with new ways of working. Moira had a simple system she used.

But, in my care, that simple system grew into a monster.

3. Set SMART goals

SMART goals are pretty well-known. In fact, my son was taught them in his middle school PE class. That’s good because there’s solid, research-based logic underlying Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time-bound goals.

I worked backward from the outcome I wanted: Not getting fired. To achieve this, I needed to publish about one top journal article per year. These journals generally have acceptance rates below 10%. However, that rate accounts for papers that are desk-rejected because they are out of the journal’s scope or not professionally done. Personally, I didn’t have the skills or infrastructure to submit ten articles a year. So I hoped that submitting 4-6 articles per year would get the job done. Even six seemed out of reach at first, so I started with the goal of four. (At the time, I was submitting one or two per year.)

It’s just simple math from there. In my target journals, papers that receive an initial invitation to revise and resubmit (R&R) have about a 50% chance of eventually being published. So I needed two R&Rs on those four submitted papers, or roughly one every six months. And I needed to resubmit those articles in a timely fashion, such that I was resubmitting at least two R&Rs per year.

But there was no way to achieve that by working the same way I’d been working.

4. Build accountability systems

I got inspiration for improving my writing from an unexpected source: weight loss. I had lost about forty pounds over two years by tracking my weight with an app. That simple act of inputting what I weighed that morning led me to reflect on why my weight fluctuated. As I connected the measure with the behaviors that triggered them, I was able to change my behavior without it feeling oppressive.

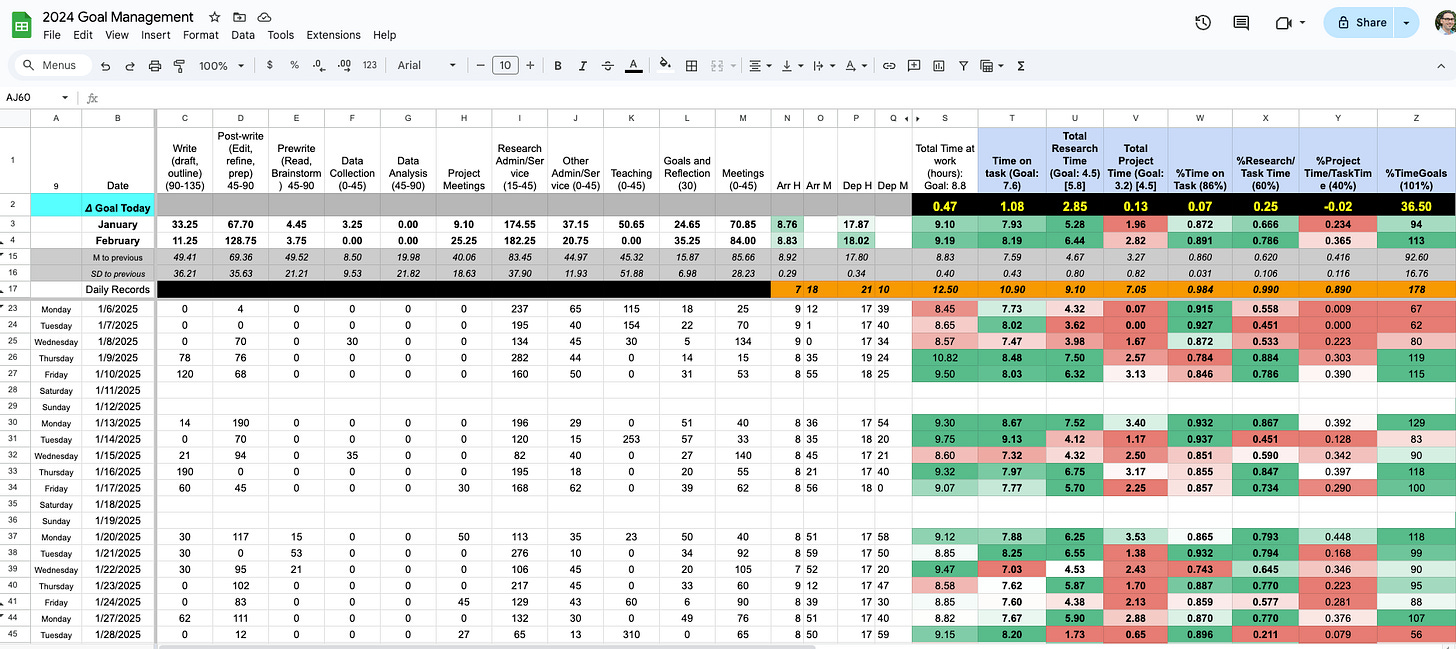

I applied the same philosophy to changing my writing habits. I would track my writing! But what should I track? It doesn’t do much good to track papers submitted or R&Rs every day. Those come every couple of months, at best. So I had to choose between two interim outcomes - words written or time spent writing.

For me, the choice was obvious. I wrote plenty of words. But I didn’t stay focused on writing what was most important. So I tracked time I spent on actual manuscript writing vs. other professorial tasks. At first, I found I was only spending about 20% of my time on actual manuscript production (about 1.7 hours from an 8.5-hour work day). That was way too low! I set a target of 40% instead (3.4 hours).

I needed to track time to figure out if I was hitting these targets. So, I started a spreadsheet in which I tracked minutes spent on research, teaching, or service. It has grown into the behemoth partially shown below (it started much smaller and simpler).

Time efficiency was important to me because I was experimenting with hard boundaries between work and non-work. I wanted to spend time with my family when they were available. So, even though it isn’t my natural circadian rhythm, I moved to a 9-5 schedule (actually, 8:45-5:45). I fought hard to work only during these times. This made the challenge easier to understand: Get the most out of those hours.

I then put specific tasks into my calendar to work on them. “Write Paragraph 1 of Theoretical Background”. I used a Pomodoro-technique type of approach, setting alarms for between 30-45 minutes at a sitting. (I do 30 right now.) When the alarm goes off, I get up and do some mini-exercise. I recenter on what I need to do next.

The system allowed me to build trust with myself. I would give myself an assignment, and I would do it. I had a much better idea of how long different tasks took. I was approaching 90% efficiency with my time, working about as much as I could without burning out. So, why worry? If this didn’t get me where I wanted to go, I wasn’t willing to do what it took to get there.

I think of this as, literally, managing myself. I give my future self tasks and goals. I track progress toward them. And I offer small rewards for achieving them.

5. Let go of your old relationship with writing

I came into academia with an artist’s mindset. (I used to be a jazz musician.) I poured a lot of myself into my work. I tried to express myself through writing. I believed that I could only write when I had 187 uninterrupted minutes in a silent place with a rare orchid and the slight aroma of toasted pumpkin seeds. I thought I was one of those slow writers who simply needed the right conditions to write.

This was all bullshit.

The book How to Write a Lot by Paul Silvia really helped me reassess my relationship with writing. Silvia argued that academic writers are not poets or novelists in need of pristine writing conditions; we are more like technical writers who produce manuals for microwave ovens. As he put it:

Writing productively is about actions that you aren’t doing but could easily do: making a schedule, setting clear goals, keeping track of your work, rewarding yourself, and building good habits. … Academic writing should be more routine, boring, and mundane than it is. … You should write like a normal person, not like a poet.

To have a new way of working, I needed to let my old relationship with writing die. I needed to break up with Artsy-Colin, delete him from my contacts, and block him on socials (at least during times scheduled for academic writing). Instead, I strove to write clearly. It didn’t matter if readers were impressed by my intellect or choice of words. It mattered that they understood.

Epilogue

I write this in the hopes it helps someone - as it might have helped me a couple decades ago. Although things are going well now, it wasn’t always this way. There were a lot of small changes along the way. I may not make the prettiest little sentences, but I get shit done. I teach writing. I got one of those sought-after book deals and wrote a goddamn book. I’ve published enough stuff to get tenure. And I want to tell you what I wish someone told me:

You’ve got amazing things inside of you. Writing is the conduit to pass your thoughts and experiences to others. It’s like an invisible pipe that makes your thoughts and experiences accessible to others. But you have to work on that pipe - keep it clean and free of too much debris. And that means flushing it out every day - by writing. By setting yourself clear goals and holding yourself accountable. To hold your writing time as sacrosanct as an appointment with your celebrity crush.

Gigs etc

I had a blast playing 91 Living Room with Suedejazz Collective at the end of January. We’re back on February 28th - pretty sure the last one sold out, so get your tickets early!

Next time

Stay tuned for a summary of the academic writing tips I’ve been posting over on LinkedIn, along with some bonus commentary, the books I’ve been reading, and perhaps a musical interlude.

Welcome (back) to The Fishbowl

[If you are a long-time reader of The Fishbowl, you may not find much new information here. This post is mostly an introduction for new readers. I’ll be publishing twice-monthly going forward, so more new content is coming soon!]

Academia can look like an individual sport, but it's really a team effort. Our writing group + my academic coach were so important to figuring out how to thrive in this profession. Love your blog.

I guess it's safe to assume you have practised a balance between academic and artistic writing habits, and displayed them here on Substack. This is my first piece I have read of yours and I could not help but smile and feel romanced with your delivery.

Cannot wait to read more.